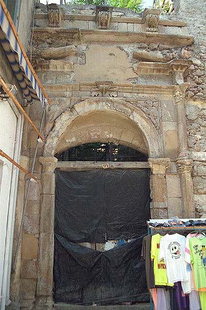

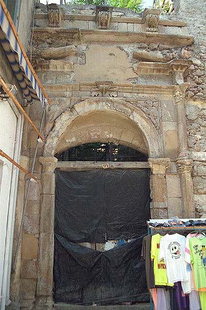

Il portale di un palazzetto veneziano, Rethimnon

In 1204 the Crusaders took Constantinople and dismantled the Byzantine Empire. Crete fell into the hands of Boniface of Monferrat, who then sold it to the Venetians for about 1000 pieces of silver. Crete was necessary to the Venetians as a cross-road for their commercial interests in the East. The Genoese, traditional rivals of the Venetians, opposed the occupation, along with the native Cretan population. During the first centuries of Venetian rule there were continuous rebellions.

The Venetian system of rule was oppressive and strictly maintained. Overlords, appointed directly from Venice, efficiently exploited the resources of Crete. Heavy taxes, low fixed prices for produce, and the confiscation of private land caused continuous local opposition and unrest.

Slowly, the Venetians relaxed their regime and permitted intermarriage and freedom of settlement anywhere on the island. With these changes, the social and economic life of many Cretans improved. During the Middle Ages, exports of corn, oil, and salt kept ports busy. Cretan wine was also widely exported and became famous throughout Europe. However, the system of serfdom and statutory labour lasted until the end of the Venetian rule.

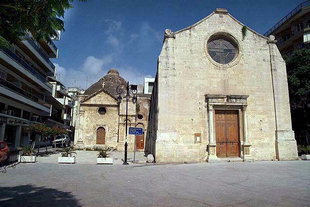

After the final fall of Constantinople in 1453, Byzantine scholars took refuge in Crete. Thus, the island became a centre for Byzantine arts. Soon, the influences of the Italian Renaissance were combined with the principles of classical aesthetics and with Byzantine characteristics, and a new school of painting, the Cretan School, was formed. During this time the renowned icon painter Damaskinos studied with Dominikos Theotokopoulos, "El Greco", at the school of Agia Ekaterini in Iraklion.

Education advanced with the development of lower and middle schools similar to those in Venice. Many Cretans studied at the universities of Venice and Padua and returned to Crete as doctors and lawyers. Monasteries, such as Moni Agarathou and Moni Vrondisi also became centres for learning and the scholar-monks of Crete became significant officials in the Orthodox Church.

As education flourished, so did the written word. The main literary figures during this time were Georgios Hortatzis, author of the dramatic work Erophile and Vincezos Kornaros with his work, Erotokritos. This is a masterpiece of Cretan literature that is still recited throughout the island.

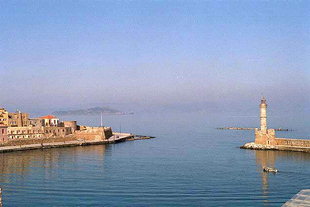

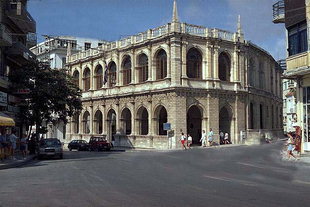

During the Venetian occupation, Italian architecture spread rapidly across the island. Cretan towns (Chania, Rethimnon, and Iraklion ) began to resemble Venetian towns, with buildings, fortresses, harbours and churches designed by Italian architects.

) began to resemble Venetian towns, with buildings, fortresses, harbours and churches designed by Italian architects.

In the sixteenth century, with the threat of Turkish invasion imminent, work began on rebuilding the large fortresses. Over the course of a century, forced labour built the "Megalo Kastro" -- the fortification of Iraklion, still standing today. All the major towns and harbours of Crete had such fortresses.

Foto di Venetian Rule:

L'entrata del Monastero di Agàrathos

Il faro veneziano all'entrata del porto, Chanià

La chiesa bizantina di Agìa Ekaterini (1555 circa) a Iraklion

La Loggia veneziano ad Iraklion

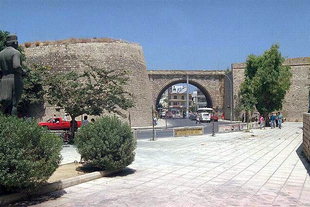

La cosiddetta Chaniòporta (1570 circa), Iraklion

La chiesa del Monastero di Agii Antonios e Thomàs

Il portale di un palazzetto veneziano, Rethimnon

| < Prec. | Succ. > |

|---|